Behavioral investing guru Terry Odean's winding path to finance

ACCIDENTAL ECONOMIST BY KIM CLARK

If you're an investor who doesn't know of economist Terrance Odean, you may be surprised by how well he knows you. Odean has been making financial headlines with his findings that the typical discount brokerage investor isn't the rational analyst assumed by economic textbooks but an overconfident, self-destructive trading addict.

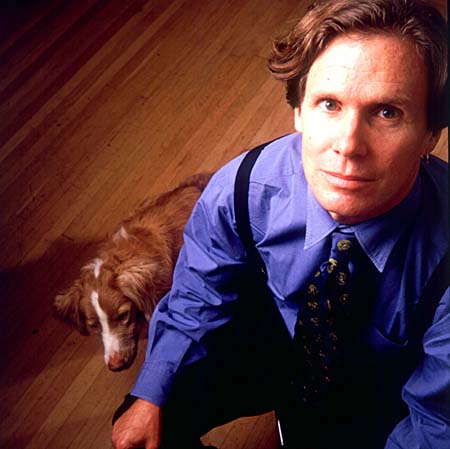

Those painful truths have thrust Odean, who just two years ago was an obscure, long-haired, and somewhat elderly graduate student, into the limelight of the media frenzy surrounding the stock market. Now sporting neatly trimmed shaggy hair and an "Isn't this a hoot?" grin, the assistant finance professor at the University of California-Davis answers almost daily calls from reporters. His studies are being accepted for publication in top academic journals. And he has won fans like William Goetzmann, director of the International Center for Finance at Yale University.

Attention getter. One reason for all of this: Odean is the only economist of this generation who has gathered a large amount of data on the behavior and profits of individual investors. That has thrust him into the center of some hot financial controversies.

And he is about to stir up more debate. In a study he's preparing with research partner Brad Barber, an associate finance professor at UC-Davis, Odean will report that people who become electronic traders generally have better than average investment profits. But when they switch to online trading, their profits fall far below average. Because online traders lose even more than the costs of commissions and trading fees, Odean suspects that online traders' early profits stemmed from luck, which turned sour as they traded more.

Another reason for the growing buzz around Odean: In a field dominated by technical drones who pump out mathematical models, Odean is a throwback to the era when economists were idealistic philosophers and eccentric characters. One of the latest bloomers in the history of economics, Odean took 49 years, hitchhikes through Europe, and a series of dead-end jobs before clambering onto the on-ramp to economic fame. "It was a circuitous route," Odean says with Minnesota-bred understatement. "I don't recommend it." Indeed, someone planning to change the way we look at investing would hardly enter, as Odean did, a Benedictine monastery at age 14 to study for the priesthood. Nor would he likely drop out of the monastery at 17, then out of college at 20. Most would also consider it poor career planning to quit a hard-won job as an actuary trainee after three boring days to drive a cab in Manhattan.

It wasn't until his 30s that Odean settled down to a computer programming job in San Francisco. He and a friend bought a year's worth of financial data to see if they could uncover new correlations. They did. The stock price of Mary Kay cosmetics (which has since been taken private), they found, predicted the price of gold. "That's when I realized the obvious," Odean laughs. "That you can come up with these [correlations] by pure chance. It wasn't time to quit our day jobs." But the experience paid off; it pushed Odean back to school to study statistics.

Odean, 37, married, with a mortgage and one child (two more would arrive later), quit his job and returned to college. While finishing a degree in statistics at the University of California-Berkeley, he became fascinated with the field of study called behavioral finance, which examines how people's emotions affect their investment decisions and performance. At 39, Odean signed up for a Ph.D. course at Berkeley's business school with the aim of specializing in behavioral finance.

This was another gamble for Odean. Behavioral finance was a field invented in the mid-1980s by a group of economists who had the temerity to challenge the theory that investment prices are "efficient," or reflect all of the information about an investment at any given time. In 1985, Werner DeBondt of the University of Wis- consin-Madison and Richard Thaler, now an economist at the University of Chicago, inspired a blizzard of studies when they analyzed stock price data to show that investors overreact to bad news and typically send prices lower than justified.

At about the same time, Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman, economists at Santa Clara University, theorized that investors were suffering because of a "disposition effect," an ego-boosting but profit-sapping tendency to hold on to money-losing investments but realize the gains on winners. Economists tended to discount these studies because the findings were often based on the results of a few dozen undergraduates investing in imaginary stock portfolios.

But Odean shrugged off the criticism. "I've felt these emotions, [such as] the desire to hold on to that loser until it comes back. It's got to be the case that other people are like this," he says.

In his naiveté, Odean thought the best way to prove his theories would be to examine investors' trading records for their performance. Odean soon learned why no one had published such an obvious-sounding study in the past 20 years. His letters to every major brokerage requesting customer data were rebuffed. They may have been worried about the kind of publicity Odean ended up generating–reports that their clients don't do as well as their advertisements suggest.

Odean became obsessed with getting the data. Parties, tennis dates, and chance meetings all became opportunities for lobbying anyone with the slightest connection to the brokerage industry. Finally, in 1994, a personal contact came through. A large discount brokerage, which Odean promised to keep anonymous, handed over the beginnings of what would eventually become a database of 78,000 randomly selected accounts (stripped of clients' names). It was the break of a lifetime.

Hot commodity. He started crunching the data and by 1997 had finished his dissertation. The next year he began publishing his remarkable findings in top academic journals. As a result, Odean became one of the hottest properties in the academic job market. He was wooed by such prestigious universities as Yale and Northwestern. But, in the end, he decided that prestige didn't matter as much as family happiness. He took a job at nearby Davis, a school that, until his arrival, hadn't been known for its behavioral finance department.

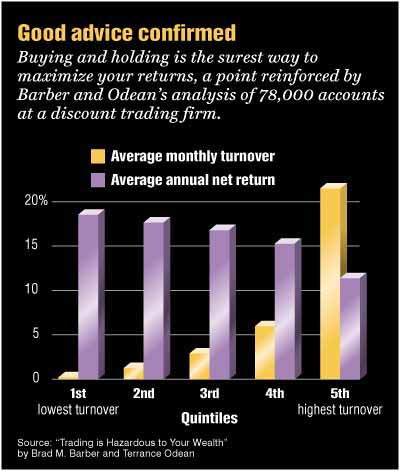

In the two years since, he has teased out of his data a half-dozen fascinating and important conclusions. He found, for example, that on average the investors he studied didn't buy and hold. Instead, they traded too much. Worse, they tended to sell their winners and hold on to their losers. In all, Odean concludes, individual investors appear to be overconfident about their abilities to pick stocks and time the market, and that hurts their profits.

Although he concedes many academics look down on those whose names show up regularly in the popular press, Odean happily gives interviews and advice. "I want to be like the dentist, and put myself out of business" by helping investors to trade smarter, he says.

While it may be possible to make money from his insights, Odean recommends that amateurs steer clear of regular trading. Most investors would do best to do what he does: simply buy and hold index funds. (Some mutual funds, however, are doing well by applying behavioral finance principles [chart].)

More important, he advises, investors shouldn't worry about returns, because money doesn't buy happiness. The best investment he ever made, Odean notes, wasn't a stock or bond. It was his Ph.D.