ACR 2015 Consumer Neuroscience Roundtable

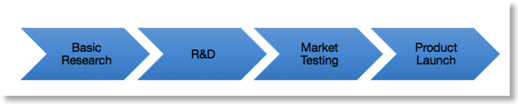

In a mature and functional product development value chain, there is a virtuous cycle where basic research creates new possibilities, which are exploited and refined to fill some need, which in turn creates more demand for basic research.

But in a new or dysfunctional one, basic researchers create possibilities that are not exploited, for a variety reasons. Alternatively, industry want deliverables that cannot be satisfied, for a variety of reasons. It’s like the old Tolstoy quote, “Every happy family is happy in the same way. Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Except instead of Anna Karenina, we get (i) moonshots in the sense of “if we can do X, everything is going to be different”, and (ii) vaporware, “everything is going to be different!

The really depressing part is that, instead of thinking strategically about closing this gap, everyone is being asked to be all things to all people. Academic researchers are told that, “Show that your methods works in the way that industry would want to use them,” while practitioners are told that, “Show that your methods work and provide scientific proof.”

Now, both of those requests are perfectly reasonable in themselves. Nobody can argue against them. But imagine if the pharmaceutical or any other field worked this way. A chemist finds some new molecule, instead of passing it along to the next part of the chain, they need to find their own disease target, then do their own trials, and perhaps then sell it to hospitals and market to doctors and patients.

THESE THINGS DON’T HAPPEN IN A VACCUM.

Okay, now the (cautiously) optimistic part. Even given so much pessimism, marketers and businesses remain intrigued and excited by neuromarketing. Even without much strategic planning, there are optimistic signs that neuroscience can indeed deliver value. Nothing like “pushing the buy button”, but something more interesting. Imagine what can happen with a bit of planning, coordination, and division of labor.

My Typical Day

Anyway, overall I found it a surprisingly difficult question, so I thought about a bit afterwards. Here’s my answer (for now). Perhaps it would help people who are thinking about entering into this area, or just help demystify what a neuroeconomist/neuromarketing researcher does.

So instead of by type of day, I thought it’s more helpful to organize some of the types of conversations I have in a single day. The actual mix varies, but I think that’s a pretty good encapsulation.

Business school faculty: This group includes consumer researchers, psychologists, economists, etc. When I first came to marketing, I would spend a lot of time finding common starting point with them, in terms of our mutual interests. It could be something like branding or pricing, but mostly it took on an almost philosophical quality about what kind of science one can do.

A lot of the time was spent on debunking and setting right expectations, like, “It would be nice if there was an irrational part of the brain, but it’s a bit more complicated than that.” Nowadays we understand each other better, so the conversation is a lot of practical. They understand what we can and can’t do, and I understand what are some worthwhile questions. In fact, these conversations led me to start this blog.

- Practitioners/Managers: I’m having these conversations more often in the past couple of years. It reminds me a lot of those early conversations with bschool faculty, which makes sense since we’re just getting to know each other.

- My lab and collaborators: This includes basically people directly involved in my researchers. It’s a pretty electic bunch of biological scientists, social scientists, biomedical researchers, and methods people. This is when I can totally geek out, a lot about designing experiments, data analysis, using and developing new methods. And grant writing, lots of grant writing. That’s the one part I envy my Haas colleagues. Most of them don’t have to write grants.

- Students (both MBA and undergrads): One of the biggest challenges for those of us moving from basic to applied science is the teaching. For me, the turning point was when I stopped teaching students the knowledge that I think they should learn, but rather the knowledge that they will want to have one, five, ten years into their careers. This has made teaching marketing, data, and applying the scientific method to business both fun and useful. Simple customer-orientation when you get down to it, but like a lot of simple things in life, those are the hardest lessons to learn.

2015 Association for Consumer Research

- How presentation of information affects consumer decisions in the real word: There is a lot of handwringing in basic sciences about the relevance of research for the "real world". Suzanne Shu presented some work on social security savings decisions and how different forms of presentation of information affects their savings decisions. Seems like a really natural area for consumer researchers. Standard economic theory provides very little guidance, and consumer researchers probably know more about this than anyone else.

Value of interdisciplinary research: Perhaps my favorite session was the roundtable on interdisciplinary research, and broadly on the future of the discipline of consumer research. My impression is that in many other fields this type of discussion is done behind closed doors by a bunch of VSPs (very serious persons), so it's refreshing to see these discussions in person. Broadly, I think this is excellent news for those of us in neuromarketing/consumer neuroscience.

- Broader training for students across disciplines: This might seem obvious, but one rarely hears that from psychology, and I dare say never from economics.

- Increasing the value of conceptual/theory work: Consumer research is almost exclusively empirical these days. This one is going to be hard to change. Biology is iin a similar position. Not sure what to do about that one.

- Need for educating reviewers and editors: I think this one is the most encouraging sign for me. There was a serious conversation about how to encourage innovative research without lowering standards. Again, seems so obvious, but really hard given the impetuousness of academics to get anyone to recognize the problem, let along think about solutions.