CMR article highlighted by NMSBA

Berkeley Science Journal Interview

The latter was a particularly interesting and insightful experience for myself. I was never one to have grand career plans or really deliberative at each step. Looking back there were definitely a number of important positive and negative aspects, but it was surprisingly difficult to articulate them. I think I could’ve done better in terms of being providing takeaways that may be relevant for them. Hopefully this is something that will become clearer as I think more about this.

What Neuroscience Can Inform Us about Brand Equity II

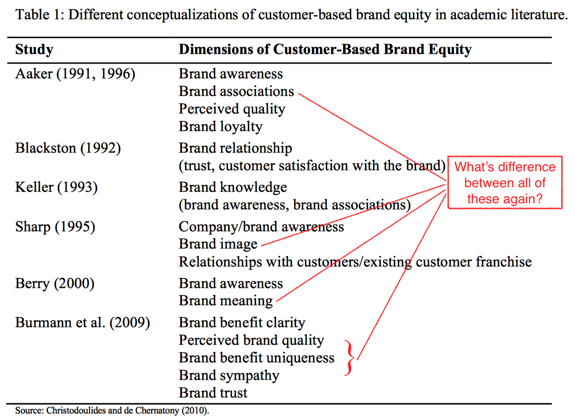

While researching for the paper, something that struck me was the lack of agreement on even basic concepts of “brand equity”. Below is a (likely complete) list of dimensions of “customer-based” brand equity proposed in the literature. (Contrasted with firm-based brand equity which is typically calculated from financial data).

What’s really striking is how they are so similar and different at the same time. I’m not trying to pull a post-modernism trick. For example, consider something like “brand awareness”, which flits in and out of the various frameworks. It clearly has some relationship with brand associations, since one can’t be aware of something that has no associations (or can it?). But what is that relationship and how is it distinct from brand associations? Trust me, it doesn’t get any better than that.

A basic contribution of neuroscience, then, is to simply provide a more rigorous framework to conceptualize these marketing typologies. No psychologist studying “knowledge”, “associations”, and “awareness” would be ignorant of the fundamental contribution cognitives neuroscience has made to these topics. I don’t think it’s crazy to suggest that the same should apply to consumer researchers. As for what I tentatively propose as a more biologically-plausible framework? That, as they say, requires you to read the paper.

More generally, I’ve found that a useful way to think about what neuroscience can contribute to marketing and consumer research is to ask, “What do consumer researchers think they are studying/measuring?” This might seem either obvious or unnecessarily antagonistic, depending on your perspective. But it is quite different from the way the questions as they are typically posed currently, which is more akin to “What can [enter your technique] tell me about [enter what marketer/consumer researcher is interested in]?” At the risk of making sweeping generalizations (which of course I will now be making), a real issue this runs into is that what marketers are interested in are often surprisingly ill-defined. I don’t think this is a knock on marketers because the real-world is complicated. Plenty of health researchers study “resilience” but nobody really knows how to define it. The real problem is in refusing to entertain the possibility that one can provide a more rigorous scientific foundation of these “fuzzy” concepts.

What Neuroscience Can Inform Us about Brand Equity

Hsu, Ming. Customer-based brand equity: Insights from consumer neuroscience. in Moran Cerf and Manuel Garcia (eds.) Consumer Neuroscience. MIT Press, Forthcoming.

This review describes how insights from cognitive and behavioral neurosciences are helping to organize and interpret the relationship between consumers and brands. Two components of brand equity—consumer brand knowledge and consumer responses—are discussed. First, it is argued that consumer brand knowledge consists of multiple forms of memories that are encoded in the brain, including well-established forms of semantic (attributes and associations) and episodic (experiences and feelings) memory. Next, it is argued that there exist distinct forms of consumer responses that correspond to distinct behavioral systems—a goal-directed system that captures valence of attitudes and preference for a brand, and a habit system that captures previously learned values but no longer reflect ongoing preferences. Finally, a neuroscientifically-grounded conceptualization is proposed with the aim of ultimately improving measurement of brand equity and its effects on financial returns.

Can neuromarketing shed its ethically dubious reputation?

Beyond the research question itself, it got me thinking again about the thorny ethical issue concerning neuromarketing.

As someone who came to marketing as an outsider, I can relate pretty well to those concerns. Indeed, for the majority of my time at Haas, my research mostly concentrated on basic science issues around economic and consumer decision-making. Part of this is due to the demands of being a junior faculty, but another part is the discomfort that I feel myself at the ostensible goals of neuromarketing.

However, it's become increasingly clear to me that, like a number of other challenges facing neuromarketing (some of which I talked about here), this is reflective of the mixed feelings that society as a whole feels for marketing, and businesses in general. Often the goals of businesses are framed as being in direct opposition to those of the consumer. This affects even the language that businesses use in talking about consumers, for example war metaphors such as “we take aim at our target market” or “we win customers".

It shouldn't be all that surprising then that there is unease about marketers having better tools in understanding our wants or predicting our behavior. Just consider the brouhaha over the Facebook emotion study.

Marketing strategists talk all the time about “aligning interests of stakeholders”. It’s time neuromarketing puts that into practice.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. In fact, there are many areas where consumer and marketers goals are quite compatible. When people talk about Apple understanding and anticipating their needs, they don’t mean that in a pejorative way.

In fact, it's positively liberating when these conflicts of interests start disappearing. I don't think I'm being naive when I say that everyone in this case wants the fans to have a good time, the Raiders, the fans themselves, and us researchers! Whatever comes out of these studies (that’s for another entry), nobody should be unhappy (except the 49ers… I kid, I kid! I, erm, like Chip Kelly?).

Marketing strategists talk all the time about “aligning interests of stakeholders”. It’s time neuromarketing puts that into practice.

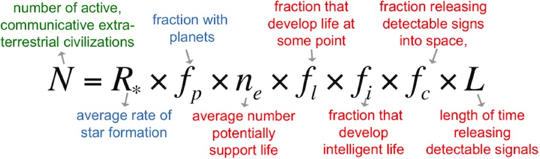

The Drake Equation

But this is just an excuse to talk about my favorite equation—the Drake Equation. And by “favorite" I mostly mean it is underrated and deserving of more praise, like how one would talk about an obscure “favorite” athlete or book. Because really, favorite equation?!

Part of what I like about the Drake Equation is its seeming absurdity at first glance. It is "a probabilistic argument used to arrive at an estimate of the number of active, communicative extraterrestrial civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy.”

On top of being about something quite out there (oh!), it also not actually all that practically useful. Recently in an In Our Time podcast about extremophiles and astrobiology, one of the guests described in the equation in the most delightful way, that, “The number N depends on

- The average number of planets that potentially support life, which WE DO NOT KNOW.

- The fraction that develop life at some points, which WE DO NOT KNOW.

- The fraction that develop intelligent life, which WE DO NOT KNOW.

- The fraction releasing detectable signs into space, which WE DO NOT KNOW.

- And the length of time releasing detectable signals, which WE DO NOT KNOW.”

But far from being a failure, it has in fact been incredibly influential. Why? Because it breaks up a daunting problem into more manageable pieces, some more manageable than others. A generation ago, we did not know the average rate of star formation, or the fraction with planets, but now we have decent ideas of those. And one can imagine that we will either find out what some of the other terms are, or break those into manageable problems that we can solve.

Simply put, the Drake Equation provides the scientific community with a strategy to make systematic progress on a difficult question. More than difficult in fact, on what is an impossible question to address with current technology.

So when I hear blanket criticisms of applying basic sciences to business or societal problems, I take heart in the fact that Frank Drake and his coauthors were able to provide a sensible scientific framework for such a seemingly absurd question.

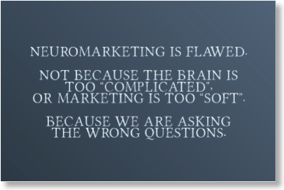

The Problem with Neuromarketing

Neuroscience either tells me what I already know, or it tells me something new that I don’t care about”.As criticisms go, it is quite persuasive. It fits with the common view of technology where the shiny new toy replaces the old cruddy way of doing things. But whereas years ago I would have jumped to take on the challenge and “show those !@#$%s”, I increasingly view such statements as something a trap, if (sometimes) a well-intentioned one.

The problem, not always but often, is that it lets someone else define the objective. Now you are solving someone else's problems, rather than what you are actually equipped to solve. Moreover, the problem with “other people’s problems” is that they are often intractable, or where the value of the returns is one-sided.

For example, I’ve had people ask for something like this, “I think our brand efforts are really reaching our target audience, but it’s not showing up in the standard metrics. Do you think you can find something in the brain that would show our effectiveness?"

Lest you think this is just practitioners lacking in scientific knowledge, here’s some from academics. “This type of behavior doesn’t make sense under any of our standard models. Maybe there’s something hardwired in our brains that produce these weird choices?” Or to paraphrase my favorite, Hey, I have this theory, can we test to see whether there’s support for it at the neural level?”

So yes, I think the current state of neuromarketing has many shortcomings, but I thnk the biggest one is that we’ve been letting others define our questions.

Upcoming Talk Schedules at Peking University

Time: 15Dec. 13:00 - 15:00pm

Location: Room 1113, Wangkezhen Building

Title

: Oscillatory mechanisms underlying decision-making under uncertaintyAbstract

: Despite tremendous recent progress in elucidating core neurocomputational components that underlie economic decision-making, we still know little about the mechanisms that coordinate the various signals within and across various brain regions. Here I will discuss results from recent electrocorticography (ECoG) studies suggesting a fundamental role of neural oscillations in governing intra- and inter-regional communication during decision-making. Specifically, we recorded local field potentials in the prefrontal cortex of in neurosurgical patients who were engaged in a gambling task. ECoG signals reflect the coordinated activity of ensembles of hundreds of thousands of neurons, and are uniquely poised to reveal fast, circuit-level computations in the human brain. We found that different aspects of the gambling game generated event-related changes in oscillatory activity across multiple areas and frequency bands. Furthermore, oscillatory interactions between lateral and orbital prefrontal regions support cognitive processes underlying decision-making under uncertainty. Together, these data highlight the importance of network dynamics in characterizing neural basis of economic decision-making.

Time: 16.Dec. 13:30-15:00pm

Location: Room217, Guanghua Building 2

Title

: Inside The Mind of the Consumer: Thoughts, Feelings, and ExperiencesAbstract

: Researchers and practitioners have long relied on self-report methods to understand how consumers evaluate, choose, and experience different product offerings. These methods, however, have remained largely unchanged since their introduction decades ago and have a number of well-known limitations. As a result, there is growing interest in brain-based approaches that may enable consumer researchers and managers to directly probe customers’ underlying thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Here I will describe recent progress and open questions in using such methods in understanding customer mindsets.Where do preferences come from?

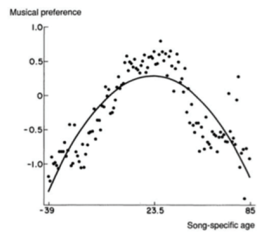

We give a few examples, but here I’ll just highlight one: "Where do our preferences come from?” If I pour orange juice on my cereal, you would probably think I’m out of my mind, but it’s not “irrational” according to standard economic models of decision-making. This type of example is sometimes used as an argument against the validity of economic notions of rationality.

Another way to look at this problem, and one that we do in the paper, is that the standard models are not so much wrong-headed as incomplete. As a consumer, my preferences are a complex mixture of my developmental history, my cultural background, and my genes. To have predictive power then, it is unlikely that we can derive our preferences from first principles alone. We need granular data, and we need to understand developmental processes.

Another example, for which I have no data but nevertheless subscribe to full-heartedly, is every soccer fan's favorite world cup is the one when they were ~10 years old. So why do we pick up certain preferences at certain ages, and how do we develop the preferences that last a lifetime? I think we can learn a lot by looking around old consumer research papers.

Haas Profile of Lab Research

If you are too lazy to read the whole thing, this is the one sentence summary of why businesses should care about what we are trying to do.

People say a lot of things, a lot of which are true but some are not. We want to develop ways to separate these.

2015 Association for Consumer Research

- How presentation of information affects consumer decisions in the real word: There is a lot of handwringing in basic sciences about the relevance of research for the "real world". Suzanne Shu presented some work on social security savings decisions and how different forms of presentation of information affects their savings decisions. Seems like a really natural area for consumer researchers. Standard economic theory provides very little guidance, and consumer researchers probably know more about this than anyone else.

Value of interdisciplinary research: Perhaps my favorite session was the roundtable on interdisciplinary research, and broadly on the future of the discipline of consumer research. My impression is that in many other fields this type of discussion is done behind closed doors by a bunch of VSPs (very serious persons), so it's refreshing to see these discussions in person. Broadly, I think this is excellent news for those of us in neuromarketing/consumer neuroscience.

- Broader training for students across disciplines: This might seem obvious, but one rarely hears that from psychology, and I dare say never from economics.

- Increasing the value of conceptual/theory work: Consumer research is almost exclusively empirical these days. This one is going to be hard to change. Biology is iin a similar position. Not sure what to do about that one.

- Need for educating reviewers and editors: I think this one is the most encouraging sign for me. There was a serious conversation about how to encourage innovative research without lowering standards. Again, seems so obvious, but really hard given the impetuousness of academics to get anyone to recognize the problem, let along think about solutions.

Neuromarketing vs. Status Quo

Here’s what each looks like to me:

- Status quo: Assume that consumer can be trusted to tell us the truth, at least most or all of the time. Otherwise it becomes difficult to convince clients to buy what we have to sell.

- Neuromarketing: Assume that consumers cannot be trusted, at all. Otherwise it becomes difficult to convince clients to buy what we have to sell.

Assume that consumers cannot be trusted.

It doesn’t require too much common sense to see what these positions are incompatible because of how each positions their products and services. The more reasonable, but maybe not as sexy or eye-ball attracting, position has got to be:

- Neuromarketing 2.0: Sometimes consumers can’t or won’t tell us the truth. We will help you figure out when those sometimes are.

Oh, we might even be able to tell you what consumers are not revealing, but don’t trust us until we can validate it in some way.