New paper on culture and genes

Nov 27, 2015 | Categorized In: Science | Consumer Neuroscience

Shinobu Kitayama, Tony King, Israel Liberzon, and I just had a review paper on the interaction between genes and culture accepted1. I'm not a cultural psychology researcher, and never thought about it much prior to talking to Shinobu. His paper on the relationship between rice and wheat cultivation on the one hand, and culture on the other, really changed how I think about the role of biology and culture.

Briefly, northern China largely relies on wheat-based cultivation, whereas souther China is largely rice-based. There are also pretty profound cultural differences. But up until now nobody bothered to quantitatively link the two and provide some rationale for why they might be connected. You'll have to read their paper for the full story, but for me it makes an incredible amount of sense, and also explains some of the regional stereotypes that every Chinese speaker would know by heart.

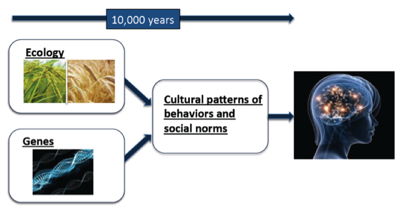

The other benefit of thinking about behavioral consequences of culture is that it allows for a much more mechanistic conceptualization of the effects of genes on culture, which is what our paper discusses. Below is one of the figures from the paper that tries to capture why social scientists interested in culture should care about biology, and why biological researchers should care about culture. Obviously this is incomplete and missing many important details, but given that culture is typically thought of as a nuisance variable in genetic and biological research, this is already an important step forward.

The other benefit of thinking about behavioral consequences of culture is that it allows for a much more mechanistic conceptualization of the effects of genes on culture, which is what our paper discusses. Below is one of the figures from the paper that tries to capture why social scientists interested in culture should care about biology, and why biological researchers should care about culture. Obviously this is incomplete and missing many important details, but given that culture is typically thought of as a nuisance variable in genetic and biological research, this is already an important step forward.

1 Kitayama, Shinobu, Anthony King, Ming Hsu, and Israel Liberzon. “Dopamine-System Genes and Cultural Acquisition: The Norm Sensitivity Hypothesis.” Current Opinion in Psychology.

Briefly, northern China largely relies on wheat-based cultivation, whereas souther China is largely rice-based. There are also pretty profound cultural differences. But up until now nobody bothered to quantitatively link the two and provide some rationale for why they might be connected. You'll have to read their paper for the full story, but for me it makes an incredible amount of sense, and also explains some of the regional stereotypes that every Chinese speaker would know by heart.

1 Kitayama, Shinobu, Anthony King, Ming Hsu, and Israel Liberzon. “Dopamine-System Genes and Cultural Acquisition: The Norm Sensitivity Hypothesis.” Current Opinion in Psychology.

Learn the rules before you break them!

Nov 23, 2015 | Categorized In: Marketing Research | Science

As someone who teaches statistics and evidence-based decision-making, I find that one of the most difficult balancing acts is to emphasize the importance of certain rules in statistical reasoning (e.g., p-values), but at the same time not emphasize them to the point of straitjacketing the students.

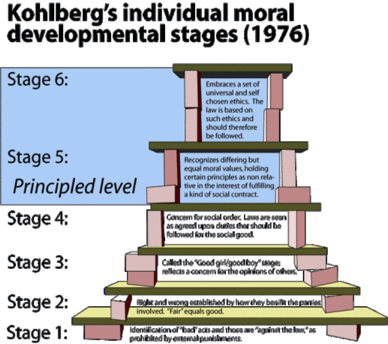

It’s the age-old rule of “learn the rules before you break them”. The problem is, different people have different standards for what “learned the rules” mean. It reminds me of the famous Kohlberg’s system on moral development stages. As children, we first learn what’s morally good and bad. Next we learn to apply these rules and apply them strictly and without exception. Finally, we learn to tradeoff between the various rules that may be in conflict.

The system holds up pretty well if we change the words “moral” to “statistical” or “data-driven”. For many people, going from Stage 4 to Stage 5 is frightening, since one is leaving the clear black and white world of rules and order. The most challenging as an instructor are those who think they are at Stage 5 but actually at (say) Stage 2. The only one we need to add is a Stage 0, which corresponds to “Stats? What's stats?”.

It’s the age-old rule of “learn the rules before you break them”. The problem is, different people have different standards for what “learned the rules” mean. It reminds me of the famous Kohlberg’s system on moral development stages. As children, we first learn what’s morally good and bad. Next we learn to apply these rules and apply them strictly and without exception. Finally, we learn to tradeoff between the various rules that may be in conflict.

The system holds up pretty well if we change the words “moral” to “statistical” or “data-driven”. For many people, going from Stage 4 to Stage 5 is frightening, since one is leaving the clear black and white world of rules and order. The most challenging as an instructor are those who think they are at Stage 5 but actually at (say) Stage 2. The only one we need to add is a Stage 0, which corresponds to “Stats? What's stats?”.

What do Donald Trump and gay marriage have in common?

Nov 13, 2015 | Categorized In: Science | Neuroeconomics

Here’s another. In both cases, everyone has a story about why that is. In Trump’s case, one I particularly enjoy is that voters are using their stated support for him to air grievances about their larger dissatisfaction, almost kind of like punishing yourself after a bad breakup.

In gay marriage, the thinking among some people is that there is a social desirability bias against opposing gay marriage.

Here’s the final one. In both cases, the stories given are quite precise and plausible (to me at least), but unfortunately neither has much support in terms of actual evidence.

Where do preferences come from?

Nov 05, 2015 | Categorized In: Neuromarketing | Consumer Neuroscience

We give a few examples, but here I’ll just highlight one: "Where do our preferences come from?” If I pour orange juice on my cereal, you would probably think I’m out of my mind, but it’s not “irrational” according to standard economic models of decision-making. This type of example is sometimes used as an argument against the validity of economic notions of rationality.

Another way to look at this problem, and one that we do in the paper, is that the standard models are not so much wrong-headed as incomplete. As a consumer, my preferences are a complex mixture of my developmental history, my cultural background, and my genes. To have predictive power then, it is unlikely that we can derive our preferences from first principles alone. We need granular data, and we need to understand developmental processes.

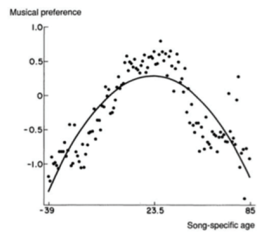

Another example, for which I have no data but nevertheless subscribe to full-heartedly, is every soccer fan's favorite world cup is the one when they were ~10 years old. So why do we pick up certain preferences at certain ages, and how do we develop the preferences that last a lifetime? I think we can learn a lot by looking around old consumer research papers.

Haas Profile of Lab Research

Haas Now just posted a profile on my lab's recent research, and how they might change the future of business and marketing.

If you are too lazy to read the whole thing, this is the one sentence summary of why businesses should care about what we are trying to do.

If you are too lazy to read the whole thing, this is the one sentence summary of why businesses should care about what we are trying to do.

People say a lot of things, a lot of which are true but some are not. We want to develop ways to separate these.