CMR article highlighted by NMSBA

What Neuroscience Can Inform Us about Brand Equity II

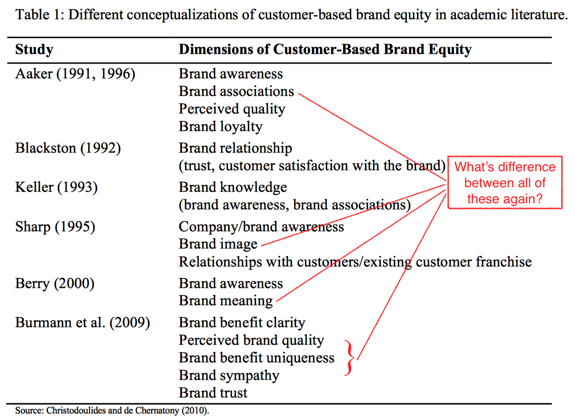

While researching for the paper, something that struck me was the lack of agreement on even basic concepts of “brand equity”. Below is a (likely complete) list of dimensions of “customer-based” brand equity proposed in the literature. (Contrasted with firm-based brand equity which is typically calculated from financial data).

What’s really striking is how they are so similar and different at the same time. I’m not trying to pull a post-modernism trick. For example, consider something like “brand awareness”, which flits in and out of the various frameworks. It clearly has some relationship with brand associations, since one can’t be aware of something that has no associations (or can it?). But what is that relationship and how is it distinct from brand associations? Trust me, it doesn’t get any better than that.

A basic contribution of neuroscience, then, is to simply provide a more rigorous framework to conceptualize these marketing typologies. No psychologist studying “knowledge”, “associations”, and “awareness” would be ignorant of the fundamental contribution cognitives neuroscience has made to these topics. I don’t think it’s crazy to suggest that the same should apply to consumer researchers. As for what I tentatively propose as a more biologically-plausible framework? That, as they say, requires you to read the paper.

More generally, I’ve found that a useful way to think about what neuroscience can contribute to marketing and consumer research is to ask, “What do consumer researchers think they are studying/measuring?” This might seem either obvious or unnecessarily antagonistic, depending on your perspective. But it is quite different from the way the questions as they are typically posed currently, which is more akin to “What can [enter your technique] tell me about [enter what marketer/consumer researcher is interested in]?” At the risk of making sweeping generalizations (which of course I will now be making), a real issue this runs into is that what marketers are interested in are often surprisingly ill-defined. I don’t think this is a knock on marketers because the real-world is complicated. Plenty of health researchers study “resilience” but nobody really knows how to define it. The real problem is in refusing to entertain the possibility that one can provide a more rigorous scientific foundation of these “fuzzy” concepts.

What Neuroscience Can Inform Us about Brand Equity

Hsu, Ming. Customer-based brand equity: Insights from consumer neuroscience. in Moran Cerf and Manuel Garcia (eds.) Consumer Neuroscience. MIT Press, Forthcoming.

This review describes how insights from cognitive and behavioral neurosciences are helping to organize and interpret the relationship between consumers and brands. Two components of brand equity—consumer brand knowledge and consumer responses—are discussed. First, it is argued that consumer brand knowledge consists of multiple forms of memories that are encoded in the brain, including well-established forms of semantic (attributes and associations) and episodic (experiences and feelings) memory. Next, it is argued that there exist distinct forms of consumer responses that correspond to distinct behavioral systems—a goal-directed system that captures valence of attitudes and preference for a brand, and a habit system that captures previously learned values but no longer reflect ongoing preferences. Finally, a neuroscientifically-grounded conceptualization is proposed with the aim of ultimately improving measurement of brand equity and its effects on financial returns.

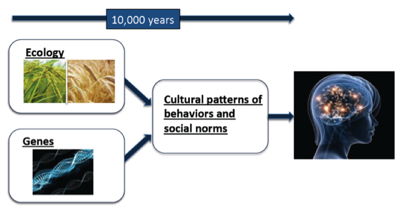

New paper on culture and genes

Briefly, northern China largely relies on wheat-based cultivation, whereas souther China is largely rice-based. There are also pretty profound cultural differences. But up until now nobody bothered to quantitatively link the two and provide some rationale for why they might be connected. You'll have to read their paper for the full story, but for me it makes an incredible amount of sense, and also explains some of the regional stereotypes that every Chinese speaker would know by heart.

1 Kitayama, Shinobu, Anthony King, Ming Hsu, and Israel Liberzon. “Dopamine-System Genes and Cultural Acquisition: The Norm Sensitivity Hypothesis.” Current Opinion in Psychology.

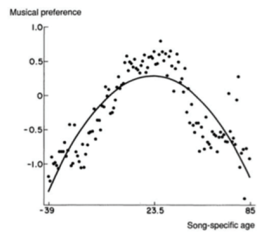

Where do preferences come from?

We give a few examples, but here I’ll just highlight one: "Where do our preferences come from?” If I pour orange juice on my cereal, you would probably think I’m out of my mind, but it’s not “irrational” according to standard economic models of decision-making. This type of example is sometimes used as an argument against the validity of economic notions of rationality.

Another way to look at this problem, and one that we do in the paper, is that the standard models are not so much wrong-headed as incomplete. As a consumer, my preferences are a complex mixture of my developmental history, my cultural background, and my genes. To have predictive power then, it is unlikely that we can derive our preferences from first principles alone. We need granular data, and we need to understand developmental processes.

Another example, for which I have no data but nevertheless subscribe to full-heartedly, is every soccer fan's favorite world cup is the one when they were ~10 years old. So why do we pick up certain preferences at certain ages, and how do we develop the preferences that last a lifetime? I think we can learn a lot by looking around old consumer research papers.