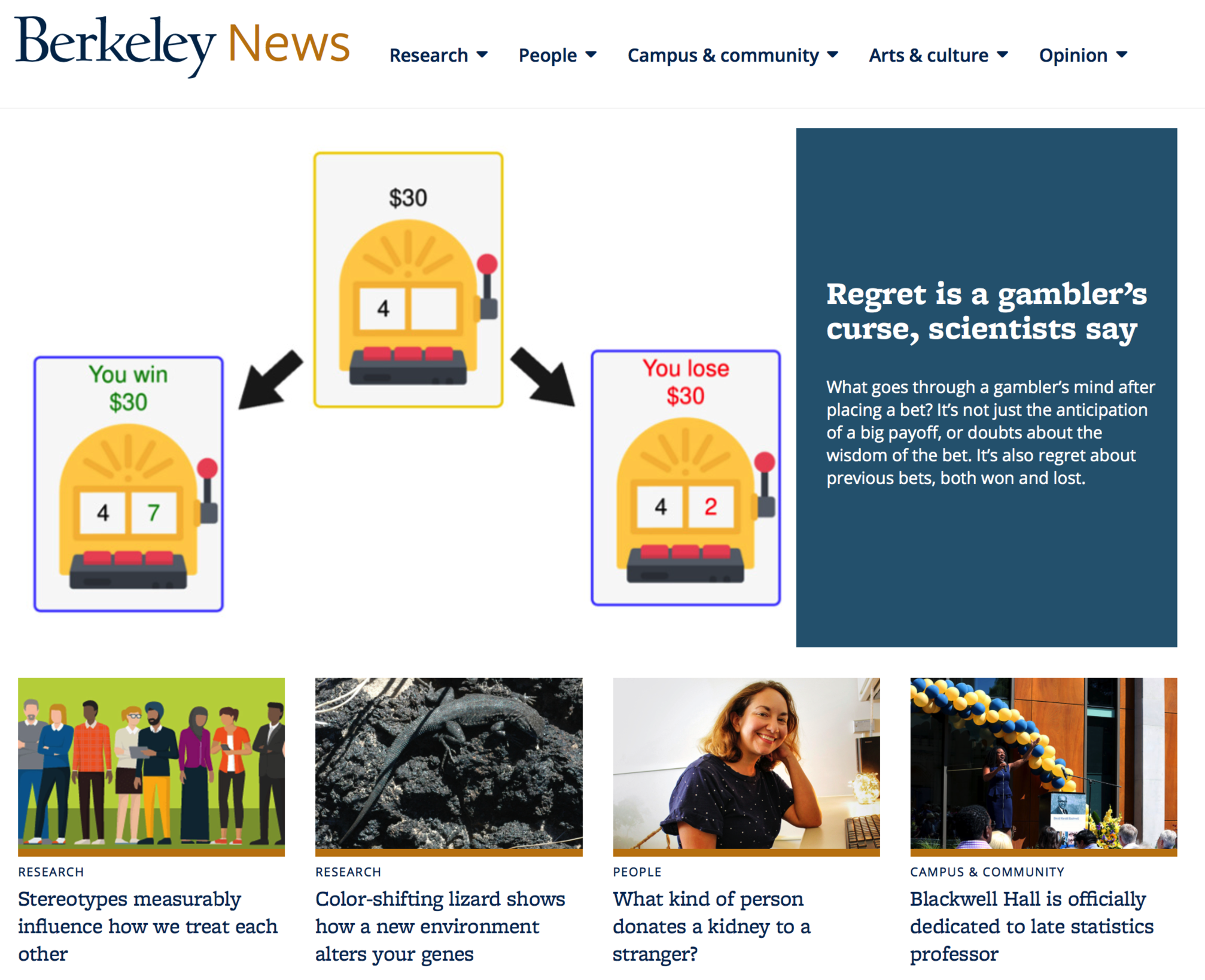

Predicting the effects of stereotypes and biases

What was the significance of this research? What did we learn?

Our study showed how to quantitatively predict how our stereotypes about other groups affect our treatment of these groups, and addressed two important outstanding questions when it comes to stereotypes and biases.

Second is the question of comparing across the advantages and disadvantages conferred by different stereotypes. For example, do stereotypes about one being "female" affect how one is treated more than say "Hispanic"? If so, how much more or less? This is particularly challenging as there are nearly infinite ways that people can stereotype different social groups.

Our results show that it is possible to do both. The basic idea is that stereotypes change the weight we place on the outcome of others. Some stereotypes increase how much we care about someone, some stereotypes decrease it. Moreover, all stereotypes can be organized along two dimensions: warmth and competence. For example, in the US, comparing stereotypes about an Irish person and a Japanese person. The Irish person is thought of as warmer but the Japanese person is thought of as more competent.

How did you arrive at these conclusions?

We developed a computational model that took in people's ratings about others' perceived warmth and competence, as well as the economic incentives that people are faced with. We then tested how people behaved toward members of other groups in laboratory experiments involving over 1,200 participants. Specifically, the degree to which certain groups were perceived as warm or competent conferred specific amount of benefit/penalty.

We then further validated this model could predict behavior in a previously published labor market field experiment involving thirteen thousand resumes. Specifically, using people's perceptions of warmth and competence, we were able to predict the likelihood that someone would be called back when applying for a job.

Voice of America: Curtailing Offensive Speech and the Fragility of Common Sense

On the one hand, the bias against certain groups is so obvious as to be common sense. On the other hand, get outside of these "common sensical" categories and things get really controversial, really fast. Are rural Americans biases against? What about working class? Is there pervasive bias against caucasians?

I think most of us have heard these and similar claims. So the question I would like to pose is, can we validate these claims in some way? Even if we find some of these claims offensive, and the people making these claims odious, can we nevertheless test these claims rigorously, and either validate or falsify them in a fact-based, data-driven manner?

Since our forthcoming paper on the topic is still under embargo, I will leave things a bit vague here, and just say that I think we are beginning to develop tools that may finally answer these difficult questions. So, as lame as it might sound, stay tuned...

CRCNS PI Meeting 2018

CMR article highlighted by NMSBA

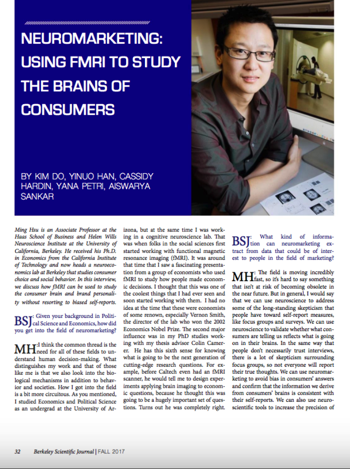

Berkeley Science Journal Interview

The latter was a particularly interesting and insightful experience for myself. I was never one to have grand career plans or really deliberative at each step. Looking back there were definitely a number of important positive and negative aspects, but it was surprisingly difficult to articulate them. I think I could’ve done better in terms of being providing takeaways that may be relevant for them. Hopefully this is something that will become clearer as I think more about this.

What Neuroscience Can Inform Us about Brand Equity II

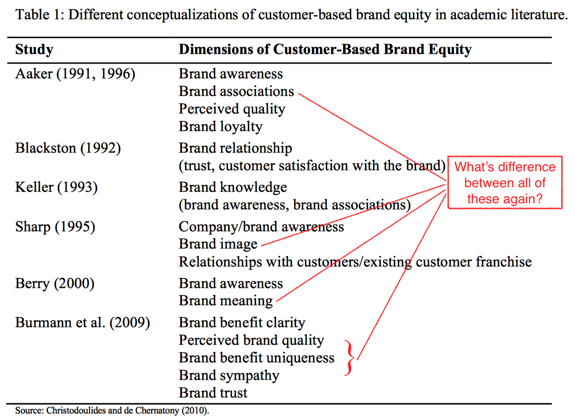

While researching for the paper, something that struck me was the lack of agreement on even basic concepts of “brand equity”. Below is a (likely complete) list of dimensions of “customer-based” brand equity proposed in the literature. (Contrasted with firm-based brand equity which is typically calculated from financial data).

What’s really striking is how they are so similar and different at the same time. I’m not trying to pull a post-modernism trick. For example, consider something like “brand awareness”, which flits in and out of the various frameworks. It clearly has some relationship with brand associations, since one can’t be aware of something that has no associations (or can it?). But what is that relationship and how is it distinct from brand associations? Trust me, it doesn’t get any better than that.

A basic contribution of neuroscience, then, is to simply provide a more rigorous framework to conceptualize these marketing typologies. No psychologist studying “knowledge”, “associations”, and “awareness” would be ignorant of the fundamental contribution cognitives neuroscience has made to these topics. I don’t think it’s crazy to suggest that the same should apply to consumer researchers. As for what I tentatively propose as a more biologically-plausible framework? That, as they say, requires you to read the paper.

More generally, I’ve found that a useful way to think about what neuroscience can contribute to marketing and consumer research is to ask, “What do consumer researchers think they are studying/measuring?” This might seem either obvious or unnecessarily antagonistic, depending on your perspective. But it is quite different from the way the questions as they are typically posed currently, which is more akin to “What can [enter your technique] tell me about [enter what marketer/consumer researcher is interested in]?” At the risk of making sweeping generalizations (which of course I will now be making), a real issue this runs into is that what marketers are interested in are often surprisingly ill-defined. I don’t think this is a knock on marketers because the real-world is complicated. Plenty of health researchers study “resilience” but nobody really knows how to define it. The real problem is in refusing to entertain the possibility that one can provide a more rigorous scientific foundation of these “fuzzy” concepts.

What Neuroscience Can Inform Us about Brand Equity

Hsu, Ming. Customer-based brand equity: Insights from consumer neuroscience. in Moran Cerf and Manuel Garcia (eds.) Consumer Neuroscience. MIT Press, Forthcoming.

This review describes how insights from cognitive and behavioral neurosciences are helping to organize and interpret the relationship between consumers and brands. Two components of brand equity—consumer brand knowledge and consumer responses—are discussed. First, it is argued that consumer brand knowledge consists of multiple forms of memories that are encoded in the brain, including well-established forms of semantic (attributes and associations) and episodic (experiences and feelings) memory. Next, it is argued that there exist distinct forms of consumer responses that correspond to distinct behavioral systems—a goal-directed system that captures valence of attitudes and preference for a brand, and a habit system that captures previously learned values but no longer reflect ongoing preferences. Finally, a neuroscientifically-grounded conceptualization is proposed with the aim of ultimately improving measurement of brand equity and its effects on financial returns.

Homo Economicus: An Apology

Homo economicus might well be described as a sociopath if he were set loose on society.

Over the past year or so, I’ve come to think that this is rather unfair to homo economicus. In particular, it also means that homo economicus is free of many of the all too ignoble parts of being human. After all, homo economicus is not sexist, racist, elitist, to name a few of the unpleasant qualities of the human species. I think it’s not crazy to say that a bit more of homo economicus might do the world some good right now.

Estimating the Proportion of True Null Hypotheses

There, it was very natural to think about the question like, “How much signal is in this set of genes?”, as opposed to “Does this particular gene have an effect?” Part of the reason is that it is much easier to establish the former versus the latter. Similarly, we can ask for each field or area, “How much signal is in this set of studies?” rather than “Is this particular study true or false?”

BTW, I looked around briefly, but not too exhaustively, to see if someone has already addressed this question, so I may well be reinventing the wheel here.

Because I am lazy, I will use the

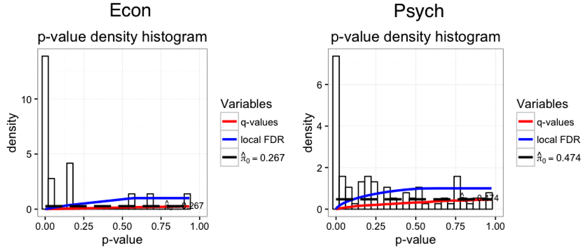

qvalue package used in the genomics field. Recently psychologists, particularly Uri Simonsohn, have developed tools along similar lines, referred to as p-curve.The common idea is that p-values under the null hypothesis is uniformly distributed, so we can estimate the departure from null by looking at the actual distribution. Replication studies are particularly useful, because unlike original publications, they provide a more unbiased distribution of the effects.

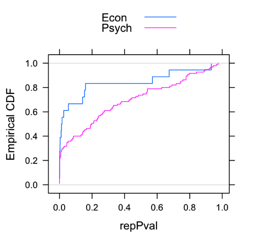

Running the q-value test, we get

pi0_econ = 0.26 and pi0_psych = 0.47. This means that the estimated proportion of true null hypotheses for economics is 26%, whereas for psychology it’s about 47%. To get an idea of why, it’s useful to take a look at the histograms. In short, there is quite a bit more mass at the larger p-values for psych than econ.

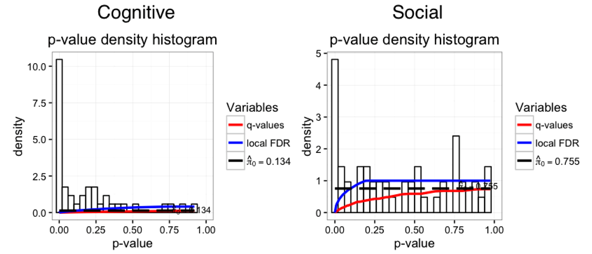

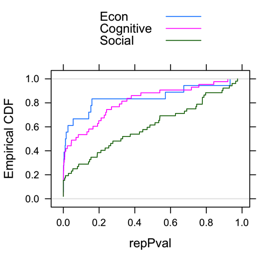

Continuing the same path as our last entry, there was a big difference between the subfields in psychology. Cognitive studies had a

pi0_cognitive = 0.13, better than experimental economics! In contrast, social psychology studies had a whopping pi0_social = 0.75! The reason? A mass of social psychology studies had very large p-values.

Lastly, I can imagine formally testing whether the 13% true null rate is significantly lower than the 26% true null rate, but I am not aware of such a test. If anyone knows, I’d be happy to test whether cognitive psych has significantly lower true nulls than economics!

Update 7/17/2015: Anna Dreber Almenberg informed me that the psychology replication data was from Open Science Collaboration, not Many Labs. In any case, here is the dataset.

Comparing Replication Rates in Econ and Psych

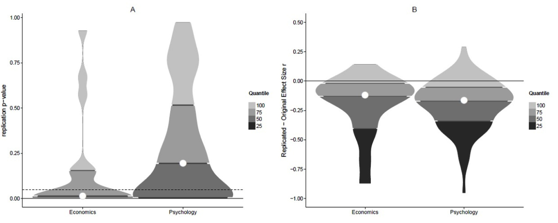

However, given that there were only 18 studies in the experimental econ set, a natural question is if the difference is “statistically significant”? A couple of psychology blogs (here and here) asked this question, and (maybe not surprisingly) came away with the answer of “no”. Euphemistically, one can say that the effects were “verging” on significance. But in this day and age, “verging” has a bit of a pejorative sense. Here is a strongly worded summary:

Still, it’s hard not to conclude that there are some differences between fields when one looks at the distribution of p-values such as the panel on the right from the figure below.Our analysis suggests that the results from the two project provide no evidence for or against the claim that economics has a higher rate of reproducibility than psychology.

Source: brainsidea.wordpress.com

One thing I didn’t like from the above analyses was the binary split at p=0.05. To get a clearer idea of their distributions, I plotted the empirical CDF of the p-values. Beyond the fact that there were about twice the mass at p<0.05 for economics versus psychology, there was a clear rightward shift in the p-value distribution, i.e., p-values in psychology appear to be systematically larger.

Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

D = 0.3807, p-value = 0.0249

alternative hypothesis: two-sided

Are All Psychology Studies Created Equal?

What’s more interesting is looking at subfields. Although the economics replication studies was too small, the Many Labs replication had about 50% each of social and cognitive psychology. If one looked at the distribution of these three groups, an interesting pattern emerges. Whereas the distribution of p-values from cognitive looks like a smoother version of the ones for economics, the one for social psych looks much flatter.

So all in all, I agree that it’s not “overwhelming evidence” that economics does better than psychology in terms of reproducibility. The sample size of 18 pretty much guarantees that, but it’s not nothing. Moreover, I think there is quite a bit of evidence that there is quite a bit of variation across fields (or subfields). If we had a few dozens areas to compare across, we would be in a much better position to say what the substantive factors are. But it seems excessive to say there is no evidence.

Full Disclosure: Colin Camerer was my Ph.D. advisor, but I think this had minimal impact here. The analyses were dead easy, and I only did this because it was curious that people got so worked up about a marginal p-value.

Can neuromarketing shed its ethically dubious reputation?

Beyond the research question itself, it got me thinking again about the thorny ethical issue concerning neuromarketing.

As someone who came to marketing as an outsider, I can relate pretty well to those concerns. Indeed, for the majority of my time at Haas, my research mostly concentrated on basic science issues around economic and consumer decision-making. Part of this is due to the demands of being a junior faculty, but another part is the discomfort that I feel myself at the ostensible goals of neuromarketing.

However, it's become increasingly clear to me that, like a number of other challenges facing neuromarketing (some of which I talked about here), this is reflective of the mixed feelings that society as a whole feels for marketing, and businesses in general. Often the goals of businesses are framed as being in direct opposition to those of the consumer. This affects even the language that businesses use in talking about consumers, for example war metaphors such as “we take aim at our target market” or “we win customers".

It shouldn't be all that surprising then that there is unease about marketers having better tools in understanding our wants or predicting our behavior. Just consider the brouhaha over the Facebook emotion study.

Marketing strategists talk all the time about “aligning interests of stakeholders”. It’s time neuromarketing puts that into practice.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. In fact, there are many areas where consumer and marketers goals are quite compatible. When people talk about Apple understanding and anticipating their needs, they don’t mean that in a pejorative way.

In fact, it's positively liberating when these conflicts of interests start disappearing. I don't think I'm being naive when I say that everyone in this case wants the fans to have a good time, the Raiders, the fans themselves, and us researchers! Whatever comes out of these studies (that’s for another entry), nobody should be unhappy (except the 49ers… I kid, I kid! I, erm, like Chip Kelly?).

Marketing strategists talk all the time about “aligning interests of stakeholders”. It’s time neuromarketing puts that into practice.

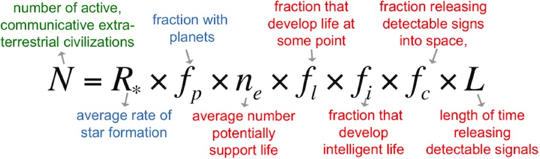

The Drake Equation

But this is just an excuse to talk about my favorite equation—the Drake Equation. And by “favorite" I mostly mean it is underrated and deserving of more praise, like how one would talk about an obscure “favorite” athlete or book. Because really, favorite equation?!

Part of what I like about the Drake Equation is its seeming absurdity at first glance. It is "a probabilistic argument used to arrive at an estimate of the number of active, communicative extraterrestrial civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy.”

On top of being about something quite out there (oh!), it also not actually all that practically useful. Recently in an In Our Time podcast about extremophiles and astrobiology, one of the guests described in the equation in the most delightful way, that, “The number N depends on

- The average number of planets that potentially support life, which WE DO NOT KNOW.

- The fraction that develop life at some points, which WE DO NOT KNOW.

- The fraction that develop intelligent life, which WE DO NOT KNOW.

- The fraction releasing detectable signs into space, which WE DO NOT KNOW.

- And the length of time releasing detectable signals, which WE DO NOT KNOW.”

But far from being a failure, it has in fact been incredibly influential. Why? Because it breaks up a daunting problem into more manageable pieces, some more manageable than others. A generation ago, we did not know the average rate of star formation, or the fraction with planets, but now we have decent ideas of those. And one can imagine that we will either find out what some of the other terms are, or break those into manageable problems that we can solve.

Simply put, the Drake Equation provides the scientific community with a strategy to make systematic progress on a difficult question. More than difficult in fact, on what is an impossible question to address with current technology.

So when I hear blanket criticisms of applying basic sciences to business or societal problems, I take heart in the fact that Frank Drake and his coauthors were able to provide a sensible scientific framework for such a seemingly absurd question.

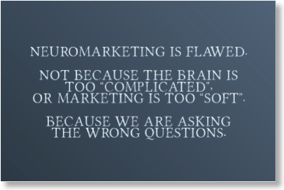

The Problem with Neuromarketing

Neuroscience either tells me what I already know, or it tells me something new that I don’t care about”.As criticisms go, it is quite persuasive. It fits with the common view of technology where the shiny new toy replaces the old cruddy way of doing things. But whereas years ago I would have jumped to take on the challenge and “show those !@#$%s”, I increasingly view such statements as something a trap, if (sometimes) a well-intentioned one.

The problem, not always but often, is that it lets someone else define the objective. Now you are solving someone else's problems, rather than what you are actually equipped to solve. Moreover, the problem with “other people’s problems” is that they are often intractable, or where the value of the returns is one-sided.

For example, I’ve had people ask for something like this, “I think our brand efforts are really reaching our target audience, but it’s not showing up in the standard metrics. Do you think you can find something in the brain that would show our effectiveness?"

Lest you think this is just practitioners lacking in scientific knowledge, here’s some from academics. “This type of behavior doesn’t make sense under any of our standard models. Maybe there’s something hardwired in our brains that produce these weird choices?” Or to paraphrase my favorite, Hey, I have this theory, can we test to see whether there’s support for it at the neural level?”

So yes, I think the current state of neuromarketing has many shortcomings, but I thnk the biggest one is that we’ve been letting others define our questions.

Field Notes from Beijing

Vertical integration of scientific research. Although disciplinary boundaries are still much more pronounced in China than the US, there is something really exciting about the vertical integration in the various disciplines. I saw a talk where a single group went through genetic screening in thousands of patients, followed up with a set of studies involving interrogation of gene candidates using animal models and in vitro approaches.

This has a definite beauty and logic to it, since many of our most pressing research questions are problem-based as opposed to disciplinary based. One can get out much of the value of interdisciplinary research by simply stacking the different disciplines together. Conversly, I can’t imagine what grant reviewer would say if I proposed to do something like this in the US.

Undoubtedly the air pollution. After a couple of days with a gloriously blue sky, courtesy of a Siberian weather system, I got the full Beijing treatment of code red air quality. That meant wearing masks even when inside. Hopefully this is the darkest hour before it gets better. I even overheard migrant workers talking about going back to their villages because of the pollution. Surely the developmental curve has caught up to the point that economic development – life quality tradeoff is moving towards the latter.

Crampons! Ice axes! Jokes about drinking your own urine! It’s ice climbing at the foot of the Great Wall!

There is something hugely satisfying and soothing about the dull thud of the ice axe into the ice. It was much more accessible than I had thought, but of course I was with serious professionals. I think I just found my new hobby.

What is (should be) the definition of gambling?

His argument is the old one that says anything requiring skill isn’t gambling. I don’t think anyone really buys that argument, since by that definition there’s nothing in vegas aside from maybe slot machines is gambling. But what I found curious was the comment from Michael Krasny, the host, that regulators didn’t have a problem with betting in the old season-long format, but only now when it became daily.

This issue of timescale rings true to me, and strikes me as being quite similar to other “vices” that we have always had trouble defining. For example, we’re perfectly fine with coffee (and for a long time cigarettes) but not many other psychoactive substances. Of course, the most famous example has to be that for obscenity, and Potter Stewart’s famous line that “I know it when I see it”.

I think the difficulty in each of those cases is finding an “objective” characteristic of the good (or I guess bad) itself (maybe I’ll just use "it"). Maybe we should instead define it from the perspective of the individual consuming “it". In all these cases, the reward itself is so incredibly impoverished, such that the pleasures of consumption is tied to some very specific aspect of the whole experience. Taking “it” away and the whole experience loses all motivational value.

In the case of coffee, people seem to consume at least two qualities. The caffeine and the taste itself (the fact that there is such a product as decaf is a pretty good indication). For cocaine, I’m guessing not. In the case of fantasy sports, there is the smack talking and the bonding experience. Take away the money, and plenty of people would still play (at least I did as a poor grad student). There's much less opportunity for that when we strip it down to a day.

This all seems so sensible that I’m sure someone has already written about this (or maybe this is what happens 12 hours into the flight). But if they have, it’s too bad that we’re still hearing the same flawed argument about requiring skill = not gambling. So here’s my proposed definition of gambling and other "vices":

An activity where immediate gratification is the sole motivation for its consumption.

Upcoming Talk Schedules at Peking University

Time: 15Dec. 13:00 - 15:00pm

Location: Room 1113, Wangkezhen Building

Title

: Oscillatory mechanisms underlying decision-making under uncertaintyAbstract

: Despite tremendous recent progress in elucidating core neurocomputational components that underlie economic decision-making, we still know little about the mechanisms that coordinate the various signals within and across various brain regions. Here I will discuss results from recent electrocorticography (ECoG) studies suggesting a fundamental role of neural oscillations in governing intra- and inter-regional communication during decision-making. Specifically, we recorded local field potentials in the prefrontal cortex of in neurosurgical patients who were engaged in a gambling task. ECoG signals reflect the coordinated activity of ensembles of hundreds of thousands of neurons, and are uniquely poised to reveal fast, circuit-level computations in the human brain. We found that different aspects of the gambling game generated event-related changes in oscillatory activity across multiple areas and frequency bands. Furthermore, oscillatory interactions between lateral and orbital prefrontal regions support cognitive processes underlying decision-making under uncertainty. Together, these data highlight the importance of network dynamics in characterizing neural basis of economic decision-making.

Time: 16.Dec. 13:30-15:00pm

Location: Room217, Guanghua Building 2

Title

: Inside The Mind of the Consumer: Thoughts, Feelings, and ExperiencesAbstract

: Researchers and practitioners have long relied on self-report methods to understand how consumers evaluate, choose, and experience different product offerings. These methods, however, have remained largely unchanged since their introduction decades ago and have a number of well-known limitations. As a result, there is growing interest in brain-based approaches that may enable consumer researchers and managers to directly probe customers’ underlying thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Here I will describe recent progress and open questions in using such methods in understanding customer mindsets.New paper on culture and genes

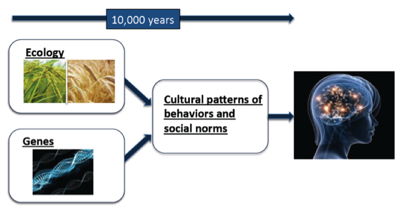

Briefly, northern China largely relies on wheat-based cultivation, whereas souther China is largely rice-based. There are also pretty profound cultural differences. But up until now nobody bothered to quantitatively link the two and provide some rationale for why they might be connected. You'll have to read their paper for the full story, but for me it makes an incredible amount of sense, and also explains some of the regional stereotypes that every Chinese speaker would know by heart.

1 Kitayama, Shinobu, Anthony King, Ming Hsu, and Israel Liberzon. “Dopamine-System Genes and Cultural Acquisition: The Norm Sensitivity Hypothesis.” Current Opinion in Psychology.

Learn the rules before you break them!

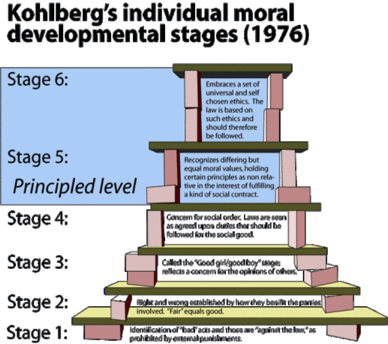

It’s the age-old rule of “learn the rules before you break them”. The problem is, different people have different standards for what “learned the rules” mean. It reminds me of the famous Kohlberg’s system on moral development stages. As children, we first learn what’s morally good and bad. Next we learn to apply these rules and apply them strictly and without exception. Finally, we learn to tradeoff between the various rules that may be in conflict.

The system holds up pretty well if we change the words “moral” to “statistical” or “data-driven”. For many people, going from Stage 4 to Stage 5 is frightening, since one is leaving the clear black and white world of rules and order. The most challenging as an instructor are those who think they are at Stage 5 but actually at (say) Stage 2. The only one we need to add is a Stage 0, which corresponds to “Stats? What's stats?”.

What do Donald Trump and gay marriage have in common?

Here’s another. In both cases, everyone has a story about why that is. In Trump’s case, one I particularly enjoy is that voters are using their stated support for him to air grievances about their larger dissatisfaction, almost kind of like punishing yourself after a bad breakup.

In gay marriage, the thinking among some people is that there is a social desirability bias against opposing gay marriage.

Here’s the final one. In both cases, the stories given are quite precise and plausible (to me at least), but unfortunately neither has much support in terms of actual evidence.