Consumer Research

What is (should be) the definition of gambling?

Dec 13, 2015

His argument is the old one that says anything requiring skill isn’t gambling. I don’t think anyone really buys that argument, since by that definition there’s nothing in vegas aside from maybe slot machines is gambling. But what I found curious was the comment from Michael Krasny, the host, that regulators didn’t have a problem with betting in the old season-long format, but only now when it became daily.

This issue of timescale rings true to me, and strikes me as being quite similar to other “vices” that we have always had trouble defining. For example, we’re perfectly fine with coffee (and for a long time cigarettes) but not many other psychoactive substances. Of course, the most famous example has to be that for obscenity, and Potter Stewart’s famous line that “I know it when I see it”.

I think the difficulty in each of those cases is finding an “objective” characteristic of the good (or I guess bad) itself (maybe I’ll just use "it"). Maybe we should instead define it from the perspective of the individual consuming “it". In all these cases, the reward itself is so incredibly impoverished, such that the pleasures of consumption is tied to some very specific aspect of the whole experience. Taking “it” away and the whole experience loses all motivational value.

In the case of coffee, people seem to consume at least two qualities. The caffeine and the taste itself (the fact that there is such a product as decaf is a pretty good indication). For cocaine, I’m guessing not. In the case of fantasy sports, there is the smack talking and the bonding experience. Take away the money, and plenty of people would still play (at least I did as a poor grad student). There's much less opportunity for that when we strip it down to a day.

This all seems so sensible that I’m sure someone has already written about this (or maybe this is what happens 12 hours into the flight). But if they have, it’s too bad that we’re still hearing the same flawed argument about requiring skill = not gambling. So here’s my proposed definition of gambling and other "vices":

An activity where immediate gratification is the sole motivation for its consumption.

ACR 2015 Consumer Neuroscience Roundtable

Oct 18, 2015

A bit delayed but here are some thoughts on the consumer neuroscience roundtable at ACR 2015. One of the notable aspects was the involvement of industrial participants. I found it alternatively depressing and invigorating. First the depressing part. The involvement of the industry participants really highlighted for me the gulf between what industry wants and what academia can deliver. This really underscores the lack of a clear value chain that connects basic researchers and practitioners.

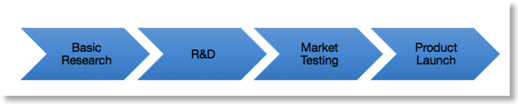

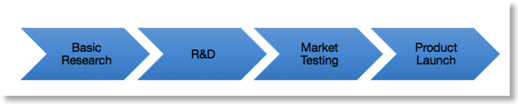

In a mature and functional product development value chain, there is a virtuous cycle where basic research creates new possibilities, which are exploited and refined to fill some need, which in turn creates more demand for basic research.

But in a new or dysfunctional one, basic researchers create possibilities that are not exploited, for a variety reasons. Alternatively, industry want deliverables that cannot be satisfied, for a variety of reasons. It’s like the old Tolstoy quote, “Every happy family is happy in the same way. Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Except instead of Anna Karenina, we get (i) moonshots in the sense of “if we can do X, everything is going to be different”, and (ii) vaporware, “everything is going to be different!

The really depressing part is that, instead of thinking strategically about closing this gap, everyone is being asked to be all things to all people. Academic researchers are told that, “Show that your methods works in the way that industry would want to use them,” while practitioners are told that, “Show that your methods work and provide scientific proof.”

Now, both of those requests are perfectly reasonable in themselves. Nobody can argue against them. But imagine if the pharmaceutical or any other field worked this way. A chemist finds some new molecule, instead of passing it along to the next part of the chain, they need to find their own disease target, then do their own trials, and perhaps then sell it to hospitals and market to doctors and patients.

THESE THINGS DON’T HAPPEN IN A VACCUM.

Okay, now the (cautiously) optimistic part. Even given so much pessimism, marketers and businesses remain intrigued and excited by neuromarketing. Even without much strategic planning, there are optimistic signs that neuroscience can indeed deliver value. Nothing like “pushing the buy button”, but something more interesting. Imagine what can happen with a bit of planning, coordination, and division of labor.

In a mature and functional product development value chain, there is a virtuous cycle where basic research creates new possibilities, which are exploited and refined to fill some need, which in turn creates more demand for basic research.

But in a new or dysfunctional one, basic researchers create possibilities that are not exploited, for a variety reasons. Alternatively, industry want deliverables that cannot be satisfied, for a variety of reasons. It’s like the old Tolstoy quote, “Every happy family is happy in the same way. Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Except instead of Anna Karenina, we get (i) moonshots in the sense of “if we can do X, everything is going to be different”, and (ii) vaporware, “everything is going to be different!

The really depressing part is that, instead of thinking strategically about closing this gap, everyone is being asked to be all things to all people. Academic researchers are told that, “Show that your methods works in the way that industry would want to use them,” while practitioners are told that, “Show that your methods work and provide scientific proof.”

Now, both of those requests are perfectly reasonable in themselves. Nobody can argue against them. But imagine if the pharmaceutical or any other field worked this way. A chemist finds some new molecule, instead of passing it along to the next part of the chain, they need to find their own disease target, then do their own trials, and perhaps then sell it to hospitals and market to doctors and patients.

THESE THINGS DON’T HAPPEN IN A VACCUM.

Okay, now the (cautiously) optimistic part. Even given so much pessimism, marketers and businesses remain intrigued and excited by neuromarketing. Even without much strategic planning, there are optimistic signs that neuroscience can indeed deliver value. Nothing like “pushing the buy button”, but something more interesting. Imagine what can happen with a bit of planning, coordination, and division of labor.