Marketing Research

Berkeley Science Journal Interview

Jan 03, 2018

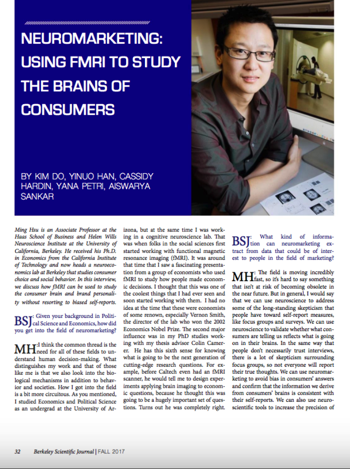

Last semester I had a very enjoyable interview with the undergraduate run Berkeley Science Journal. The interview is now published online. The students asked me about some of the practical applications of neuroscience to business practice, as well as my own career and advice for undergraduates interested in this area.

The latter was a particularly interesting and insightful experience for myself. I was never one to have grand career plans or really deliberative at each step. Looking back there were definitely a number of important positive and negative aspects, but it was surprisingly difficult to articulate them. I think I could’ve done better in terms of being providing takeaways that may be relevant for them. Hopefully this is something that will become clearer as I think more about this.

The latter was a particularly interesting and insightful experience for myself. I was never one to have grand career plans or really deliberative at each step. Looking back there were definitely a number of important positive and negative aspects, but it was surprisingly difficult to articulate them. I think I could’ve done better in terms of being providing takeaways that may be relevant for them. Hopefully this is something that will become clearer as I think more about this.

Learn the rules before you break them!

Nov 23, 2015

As someone who teaches statistics and evidence-based decision-making, I find that one of the most difficult balancing acts is to emphasize the importance of certain rules in statistical reasoning (e.g., p-values), but at the same time not emphasize them to the point of straitjacketing the students.

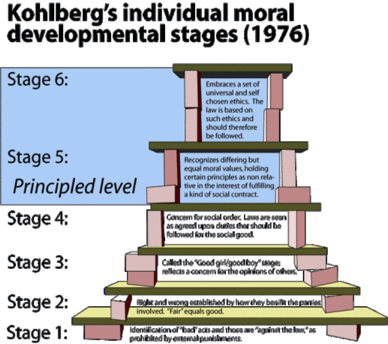

It’s the age-old rule of “learn the rules before you break them”. The problem is, different people have different standards for what “learned the rules” mean. It reminds me of the famous Kohlberg’s system on moral development stages. As children, we first learn what’s morally good and bad. Next we learn to apply these rules and apply them strictly and without exception. Finally, we learn to tradeoff between the various rules that may be in conflict.

The system holds up pretty well if we change the words “moral” to “statistical” or “data-driven”. For many people, going from Stage 4 to Stage 5 is frightening, since one is leaving the clear black and white world of rules and order. The most challenging as an instructor are those who think they are at Stage 5 but actually at (say) Stage 2. The only one we need to add is a Stage 0, which corresponds to “Stats? What's stats?”.

It’s the age-old rule of “learn the rules before you break them”. The problem is, different people have different standards for what “learned the rules” mean. It reminds me of the famous Kohlberg’s system on moral development stages. As children, we first learn what’s morally good and bad. Next we learn to apply these rules and apply them strictly and without exception. Finally, we learn to tradeoff between the various rules that may be in conflict.

The system holds up pretty well if we change the words “moral” to “statistical” or “data-driven”. For many people, going from Stage 4 to Stage 5 is frightening, since one is leaving the clear black and white world of rules and order. The most challenging as an instructor are those who think they are at Stage 5 but actually at (say) Stage 2. The only one we need to add is a Stage 0, which corresponds to “Stats? What's stats?”.

So you CAN manage what you can't measure?

Sep 06, 2015

If You Can’t Measure It, You Can’t Manage It.

Many of us have heard of the phrase, "If You Can’t Measure It, You Can’t Manage It." It's a fun quote, and is becoming increasingly popular in this age of big data. It also has a halo of authority to it, having been attributed to gurus like W.E. Deming or Peter Drucker. I was going to use it in a paper, and casually figured I'd find out who (if either of them) actually coined the phrase.

Little did I know that in fact: (i) Drucker didn't say it, (ii) Deming didn't say it, (iii) Deming said something similar, but meant something completely the opposite.

The actual quote, by Deming, is, "It is wrong to suppose that if you can’t measure it, you can't manage it—a costly myth".

I'm sure there are multiple constructive takeaways here, but what I want to know is who the !@#$% is responsible for twisting this into its current meaning?!

Who wouldn't want a faster horse?

Aug 23, 2015

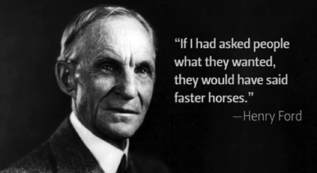

These days, the sentiment is captured most famously by Steve Jobs, who once said, “Customers don't know what they want.” Of course the actual sentiment goes back much, much farther. One of my favorites is from Henry Ford, who said, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

On the other hand, when it comes to actually doing marketing research, I would say that more than 90% of the students use and rely heavily on self-report measures. And you know what, for the most part they turn out great!

So what's going on here? Are we instructors just great at indoctrinating students? That'd be a great skill to have, but what's actually going on is that the students gain a more nuanced appreciation for what self-report can and cannot tell us. If we parsed Ford's statement a bit more, we can actually generate two insights (or more realistically, hypotheses). One is that people want something faster (okay, not exactly earth shattering news), but the second is that people are bound up in the past, and have little insights into how to actually deliver these features. To a savvy entrepreneur, this should raise all sorts of interesting additional questions about challenges and opportunities in introducing a new product.

Of course, not everyone has taken a marketing research course, and not market researchers still have considerable difficulty in convincing people of the validity of their insights. The good news though is that (i) my job is safe for a while, and (ii) there's plenty of room for improvement.

Science of Business, Business of Science

Aug 11, 2015

What is this blog about?

Two things.

1. Science of business: How can we use science to improve the current state of managerial practice, foster innovation, and reduce ethical violations? This includes scientific thinking for example through the use of data and experimentation. It also includes attempts to introduce entirely new types of data from the natural sciences, such as neuroscience and genetics. What are the areas of promise, of hype? How should we evaluate claims? How can we make progress?

2. Business of science: How can we improve efficiency and effectiveness of current scientific enterprise? Scientists are increasingly being asked to show the bottom line impact of their research, but how should we measure value of scientific research? How do we balance competing demands of basic and translational research?

Why do we need yet another blog about this?

Because these topics don’t seem to be discussed much in the blogosphere. Email me if you think someone is doing it better. I will either a) try harder, b) fold and use the time for something more productive, or (c) respond with some snarky defensive response (I kid, I kid!).Why are you qualified to write this?

Through some interesting and not-so-interesting career quirks, I ended up with training in economics, neuroscience, and psychology, and am now teaching at a business school. This means that I spend part of my day wearing my bschool hat, which involves me thinking and teaching marketing, especially topics like marketing research and the role of data in business. The rest of the time is spend with me wearing my basic scientist hat, where I direct the Neuroeconomics Lab, where my research team and I conduct research on the neuroscience and genetics of economic decision-making.Over the years, I find myself increasingly comfortable at putting on my bschool hat while thinking about science, and putting on my science hat while thinking about business. I’ve also come to realize that there is a lot of each area can learn from the other, hence this blog.